Clicker here to read the full story on UCLA Newsroom!

Celebrating 50 years!

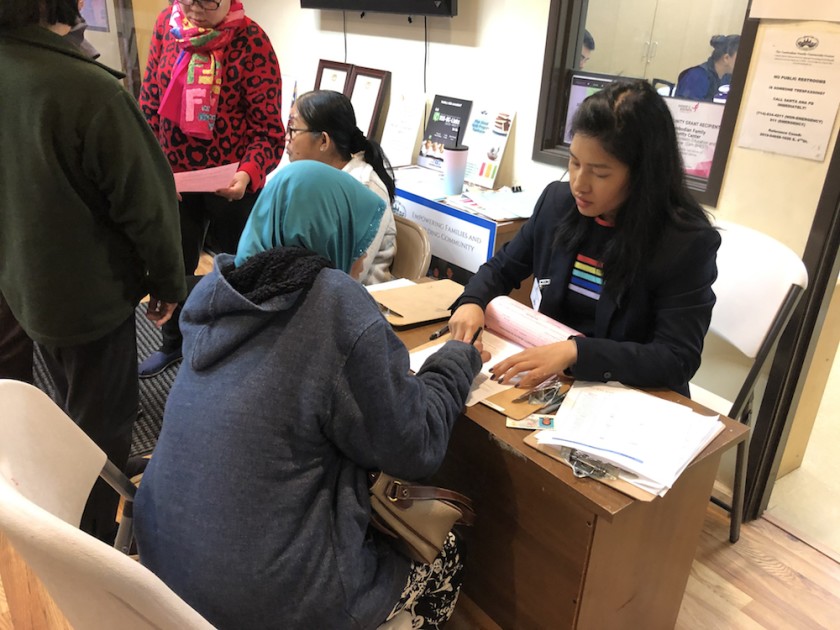

Karen Umemoto sees the UCLA Asian American Studies Center as source of memory, progress and most importantly, access.

The center, its collaborators and collections, seeks to preserve the experiences, struggles and accomplishments of Asian American peoples from multiple backgrounds, a mission that is uniquely served at UCLA amid a city that is home to communities of Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Pilipinos, South and Southeast Asians, Pacific Islanders and others.

“The center is not only a legacy institution, but continues to carve new terrain for the field and our future,” said Umemoto, who currently holds the Helen and Morgan Chu Endowed Director’s Chair of the Asian American Studies Center, which is part of UCLA’s Institute of American Cultures. All four of UCLA’s ethnic studies centers, which together make up the institute, are marking their 50th anniversary alongside UCLA’s centennial year.

For all its achievements in its first half century, Umemoto knows there is more to be done. Her plan is to expand access to knowledge and influence on behalf of the constituencies that demanded its creation in 1969, and that, despite progress, still face many of the same challenges and stereotypes.

UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center is the largest and one of the longest-running research centers of its kind in the United States with more than 60 affiliated faculty. It offers more than 30 research grants, scholarships and academic prizes each year. The center publishes two journals annually, “Amerasia Journal” and “AAPI Nexus,” as well as books, almanacs, directories, biographies and reports. It is also home to robust special collections and archives particularly related to Asian Americans and their experiences.

“We have all this research, but so much of it stuck behind a paywall or otherwise out of reach,” said Umemoto, who is also a professor of urban planning. “We’ve produced a lot of new knowledge, but we haven’t moved the needle enough when it comes to sharing it with the rest of the world. Access to what university ethnic studies centers and departments produce is so often limited to the privilege of college elites.”

To break down those barriers, the center recently launched the “Asian American Studies in Every Home” digital initiative with the creation of a media platform that will make ethnic studies scholarship, archives and curricular materials freely available to educators. It will include digital archives, narrative content, multimedia resources, and curriculum templates for secondary and post-secondary school students packaged in an open-access, easy-to-use online format.

The online interface, called “Storybooks,” could be employed for all kinds of research, publications and topics in all ethnic studies disciplines, she said.

“We have a lot to offer and want to make sure teachers have the ability to access information that will help them share accurate and compelling perspectives of people from Asian and Pacific Islander backgrounds,” Umemoto said. “I really believe in the power of knowledge in quelling misconceptions and building a more inclusive society.”

Courtesy Umemoto family

Physical education class at Manzanar, one of the U.S. concentration camps for Japanese Americans during WWII. Hank Umemoto, father of UCLA professor of Asian American studies Karen Umemoto, is on the far right at age 14.

.

The first storybook focuses on the book “Mountain Movers: Student Activism and the Emergence of Asian American Studies,” created in collaboration among UCLA, San Francisco State University and UC Berkeley about the concurrent founding of Asian American studies centers at all three schools in 1969, starting at San Francisco State.

The book is a collection of oral histories from nine remarkable student leaders reflecting on their tenacious efforts to advance curriculum and research imperatives that would address intersecting challenges facing their communities.

One of the essays in “Mountain Movers” is by UCLA alumna Amy Uyematsu, who while attending UCLA found some of the first classes offered at any university that addressed the experience of Asian Americans, including Japanese Americans after the World War II internment camps. These classes helped Uyematsu channel her rage at the inequities her own family faced around that time and the pervasive racism she experienced growing up in predominately white towns as a third-generation Japanese person. In high school, her fellow students didn’t believe her when Uyematsu told them about the Manzanar internment camp, because the forced relocation of Japanese Americans to prison camps wasn’t being taught yet as part of WWII history.

Uyematsu joined the fight for more research, teaching and community involvement, pushing against the stereotype of Asian Americans as complacent or content to be high academic achievers but second-class citizens. She became one of the first staff members of the Asian American Studies Center.

More than the ‘model minority’

“We rejected the image of Asian Americans as a ‘model minority’ — something which we are still fighting against 50 years later,” she wrote. “Being able to fight inequities through education would prove thrilling, challenging and fulfilling.”

Asian American students definitely continue to face the narrative of being academic overachievers, said Erin Khuê Ninh, a fellow and visiting scholar at the center. She’s working on a book titled “Passing for Perfect: College Impostors and Other Model Minorities.”

Mike Fricano/UCLA

Manzanar is now a National Historic Site.

“It’s this racialized idea that East Asians, South Asians and Southeast Asians are ‘supposed’ to live up to an academic ideal, according to U.S. society and also to many in their immigrant communities,” Ninh said. “As top students from their high schools, Asian Americans who enter UCLA, or other schools, are more than likely to have encountered the paradigm of the model minority as things they are expected, themselves, to believe and then perform.”

This narrative potentially affects a lot of students. Slightly more than 28% of undergraduates in the 2018–2019 school year were from Asian American or Pacific Islander backgrounds, according to the UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

One of the things UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center, and Asian American Studies departments in general, provides is a new way of looking at this narrative for young scholars, Ninh said.

“They do important work in explaining why the model minority narrative exists: historically how it came to be, whom it benefits, why some people, including many Asian Americans, take it for truth,” she said. “They do life-saving work when they show what its costs, what the flip side can be, like heightened rates of anxiety, depression, suicide, an unsustainable perfectionism. All of this takes a toll on who young people are allowed to become, if they follow its dictates to the letter.”

Capturing the history of the center

Creating a space of memory through an archive that showcases the commitment and passion that drove the creation of the Asian American Studies Center in the first place, is part of ensuring the mission stays on course, Umemoto said.

One of the first things she did upon becoming director of the center in 2018 was launch an oral history project called “Collective Memories” that documents the experiences and impact of the founders of the center. The first 10 videos are already online and Umemoto plans to have 50 stories completed by the end of the 2019–2020 school year.

They were produced by the Center for EthnoCommunications, which operates under the Asian American Studies Center umbrella, and is an element that sets UCLA’s center apart from its peers. The creative digital and filmmaking enterprise was part of the center’s original work and over the years has provided support for more than 200 projects that document, preserve, and allow for the creative expression of diverse ethnic experiences.

Renee Tajima-Peña, the director of EthnoCommunications, is currently producing a PBS docuseries titled “Asian Americans,” which will air in Spring 2020. In March, the center will host a three-weekend film festival in partnership with the UCLA Film and Television Archive that opens with its premier screening.

“Visual storytelling has always been and will always be an important part of the center’s work on behalf of communities,” Umemoto said.

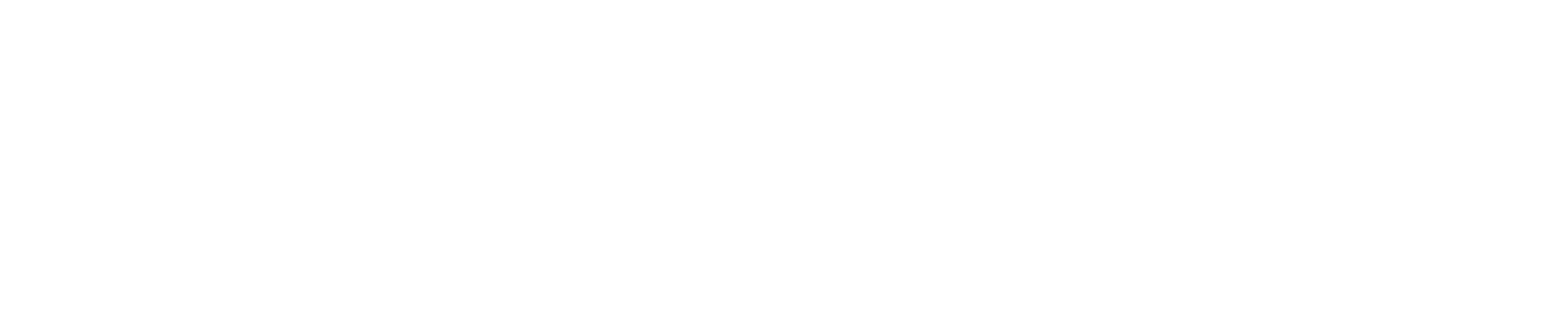

Another major project Umemoto has launched is called the Asian Pacific Policy Research Initiative. In November 2019, the center hosted the “Power to the People Conference” that brought together 300 students, faculty and members of local community groups for a series of talks and workshops on contemporary social issues, from immigration to gentrification. Umemoto and the center’s staff and faculty hope the conference will catalyze collaborative efforts to influence public policy and educate lawmakers to understand and address the needs of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities.

“We hope we have ignited a spark of inspiration to connect researchers with community groups in order to address problems like growing xenophobia, health disparities and homelessness,” Umemoto said.